Pioneering placemaking advocate who wears many hats. In this interview Hans Karssenberg talks about his practice as a planner with a focus on people and places, how transitions are pushed forward and what elements does best cities have in his opinion. Hans is the partner, founder and public developer at STIPO, which is based in Amsterdam, Athens and Milan. Hans works in different cities around the globe provide an insight to sustainable city making with the middle up down approach.

Tell us a little bit about yourself

I am an urban planner and founder of STIPO and many urban development initiatives, among others placemaking. I am someone who profoundly loves the complexity of cities and to be challenged by cities. My mission is to make a contribution in being impactful in sustainable urban development.

Being interested in cities stems back to childhood, even though my parents adducted me from city life to suburban life when I was six years old – longing back for the city even stronger until I moved back to Amsterdam. Jokes aside, I think that many urbanists have these similar personal qualities, the love for urban environments, the challenges they pose, the impulses they give. I really like exploring new cities to get these impulses and be inspired by them.

I studied urban planning in the university of Amsterdam in the late 80’s and started to collaborate with my teacher Geer Koopmans. His notion on urban planning that it can be a very impactful and very creative profession inspired me a lot. We both shared an anger towards the terrible quality of urban environments of the previous decades, especially the 80’s. The planning was not sustainable at all and as a result, many developments of those times are now being demolished – and to demolish something built 30 or 40 years ago is of course not sustainable at all either. We started our collaboration based on the mutual ambition to change this course of urban planning. In 1995, we decided to take the step out of the university to be able to work on this professionally and founded STIPO as an independent impact first team where I have worked since. My work keeps changing: the contexts changes, challenges in cities change, your knowledge deepens, networks change and evolve and new people bring new ideas and new directions – this is what makes it so interesting.

I really like exploring new cities to get these impulses and be inspired by them.

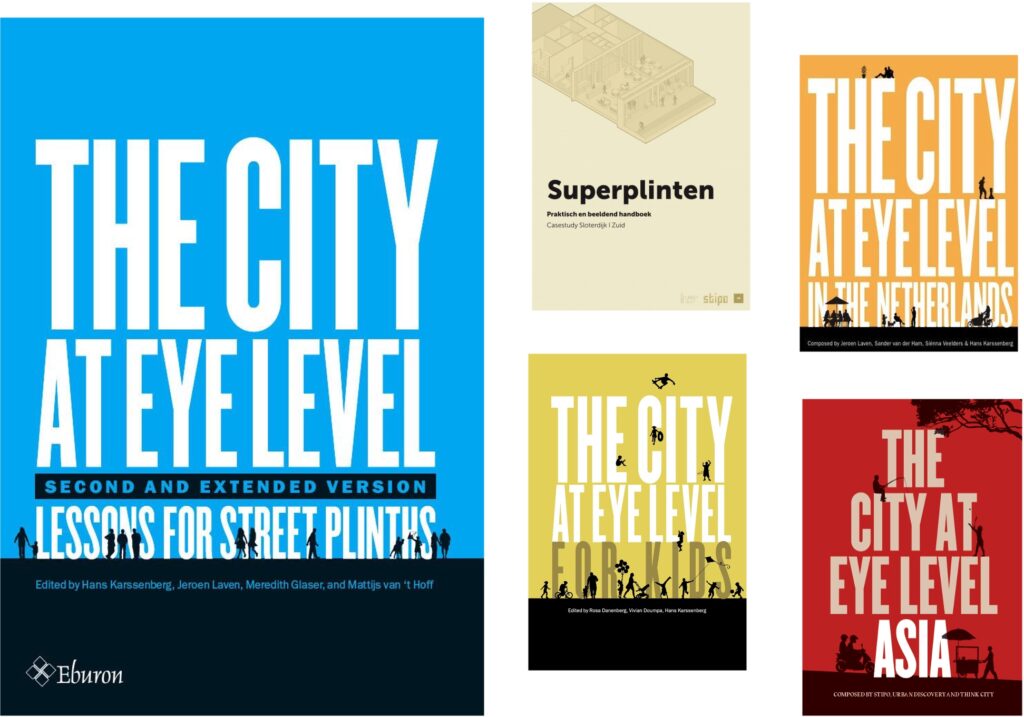

We work in practice and innovate in areas sustainably with local communities. We then like to take these lessons and use them for larger scale systemic change. If you want systemic change you need to be networked. That is why we took the initiative for the network Placemaking Europe, which STIPO initiated, but became an independent body for promoting placemaking and bringing placemakers together across Europe and worldwide – now with 11,000 participants throughout Europe, and growing. You also need to deepen and share knowledge. This is why we set up knowledge programs such as The City at Eye Level research, and share it through open source publications. And you need to create new planning and investment infrastructures. This for instance led us to initiate the Stadmakersfonds to help Dutch placemakers to buy buildings and land, take them out of speculation, and help them to turn the temporary actions into permanent to be impactful in their own neighbourhoods and not just during the warm up phase of urban development. We have until now helped 6 of such schemes to sustain themselves and grow their impact and are now taking the step towards the next 6 in the coming years, aiming to grow to a nationwide fund, and stimulating European collaboration with likeminded funds.

Why did you become an urban planner – or how should we title you?

It’s good to highlight that in the Netherlands urban planning is considered a social science and the combination of social and physical is deeply embedded into the planning culture. Of course, the profession also has a very technical side and regulations-focused sides. For me however, in essence, urban planning is very much about understanding the needs of people and translating these insights into the physical environment. I also think that the economical and cultural development are very much part of that – so for me it’s super mixed and that’s where we always get in trouble: how to label ourselves and what is what we actually do? I would outline that it’s not strictly urban planning for me, it is a holistic approach to urban development with my head in the clouds and feet on the ground in other words plan for long term but also do for short term.

That ambition of mine is probably what led me to placemaking and why I love it very much as part of our ways of working. It makes you a much more complete person as a professional when you bring your personality and character out, which are needed to making things happen in a personal collaboration with other people. Placemaking to me has a language of understanding the public space as a social space primarily, and not merely a space which has to be designed from a physical point of view. I was looking for peers with this approach for a long time, and then 15 years ago I met Fred Kent and Kathy Madden (Project for Public Spaces, PlacemakingX, The Social Life Project) and thought “Wow! There are people who already have such a vast body of knowledge on this!”.

Having said that, I would not call myself a placemaker because I do so many other things, but placemaking is in my toolbox where we take the value of placemaking as an approach for example in the long term urban planning projects. So, to recap, perhaps an urbanist is a shortest answer to what I am and do.

Last time we met, we talked about frustration being a powerful driver for change – something which has partly led us both to start our practices. Can you tell a bit more about that and what are the other drivers for systemic change?

We are in a system, which is not catering for the actual needs we have in our cities – so, we have to change the system. This could be considered to be a very abstract goal, however we like to work in the field of systemic change by organising it into smaller parts, learn from them and scale them by taking the lessons out to the larger systems. For example, we are have been working on a placemaking project in the Kolenkitbuurt, one of the neighbourhoods with challenges in Amsterdam and involving the residents in improving their neighbourhood. The neighbourhood has physical, economic and social challenges – but also a very strong social community with deeply involved initiatives that you need to understand before you do anything. The people there have said they would like to have places to meet each other as the community, despite its challenges, has a very collective spirit. This is the placemaking-mindset, although the citizens themselves would perhaps not label it as such. Mediating this process involves facing struggles to get the public space department of the city of Amsterdam committed to create places together with the residents rather than top-down. So we are constantly learning very valuable lessons which we are then further sharing with out network of Cities in Placemaking in Placemaking Europe, for example. This is in my view, one of the key elements of systemic change, to organise yourself in larger groups and to learn a lot from those groups and inspire and strengthen each other in our positions, and then turn it into local impact together with local communities in a very sustainable way.

Interestingly Placemaking Europe network started as a grassroots network with a maker-energy – and I think, we still have that. About 70% of the participants in the last Placemaking Week Europe 2023 in Strasbourg were practitioners, but the great thing also was that there was also more than 100 participants from municipalities. This means we are opening up the system to cities and municipalities. That’s why we have also launched the Cities in Placemaking program, to embrace placemaking in their system and to learn from others. I think that’s a great example of feet on the ground and zooming out from these experiences and lessons to try influence the system in a positive way. A next step is to open up the system to real estate developers with Place-Led Development.

What comes to the frustration and founding STIPO – yes, we were very frustrated with the urban planning of the 80’s, and then turn that frustration into a driver for change. I think there has been a lot of improvement since: there is a lot more awareness of good social life, good public spaces, good city at eye level and placemaking – but still I would say that about 90% of what is being built today, does not meet the requirements of liveable cities. We are still not there and that drives us forward: we would like to get to the point where that number is only 10%, where human scale, social life and the city at eye level are mainstream.

What do you think is the hardest challenge or slowest transition which slows down this positive development? There is also discussion about the profit-driven urban development which might use placemaking as a tool, but it’s not embedded truly into the planning.

We face many very complex transitions. Private car ownership is one of the biggest obstacles for human scale sustainable cities. It’s a politically very sensitive issue and it’s also a societal issue, which makes it a very challenging transition. On the other hand, we see cities working through this transition by tapping into the energy and knowledge of the community, like the great example of Milan which has introduced 50 new public squares in just three years, together with the local communities, with their Piazza Aperte program. The city recently completed a second round of the initiative receiving about 200 proposals. That is a vast amount of squares and a great example of working with communities being impactful and significant.

A second challenge is the aim of short term profit which developers are after, however it’s too easy to put that only on the developers, because we have designed the system together and many urban development funding schemes are often about short term profit. If you look more carefully into the good urban development examples, they very often have one thing in common and it’s what I like to call “slow money”. Those projects have their return of investment set not for 10 years time but for 40 to 100 years. This means that a lot of the values we stand for and the elements that lead to more sustainable environment in the broader sense of the word are at the centre of the development: local communities are involved, there is sense of ownership, there are good public spaces, there is great soul for the city, it’s mixed use rather than mono functional spaces. All of these are elements of sustainability in its broader sense: the elements necessary to make areas function well for 200 years, and not be demolished after 30 years. If we manage to redefine the pace of the return of investment, then all of a sudden a lot of these ideas we fight for start to make sense financially as well and there will be financial incentives too. There are some great examples on this already, but of course, it’s not the mainstream yet. We are now working with the City of Almere to implement this for a new neighbourhood of 35,000 homes and 25,000 new jobs, changing the area business case from a scope of 10 to 40 to 100 years.

Changing our historically grown planning system is part of the transition too. Modernism has had a big impact in the planning culture and while it has many good qualities such as aiming for healthier, more liveable and green cities, it was also largely funded by the car industry. Most importantly, modernism has one fundamental mistake by treating human beings solely as rational beings. I think we now know enough from the modernistic experiences of the past decades, that it doesn’t work like that. We are human beings, with two parts of our brains, we are complete persons and we just don’t only want to act functionally in our cities, going functionally from one place to another. We want to be our environment to be inspiring, we want to be emotionally connected and feel creative in our environment. So we need a more complete and holistic approach to urbanism while acknowledging that modernism is deeply embedded into our planning culture, construction industry, regulations and so on.

We want to be our environment to be inspiring, we want to be emotionally connected and feel creative in our environment.

A third big factor is shifting more to the triangle relationship of what we call software (urban life), hardware (design) AND orgware (co-investing networks): if you want to go through all the complex transitions that our cities face, you need to tap into the knowledge of wisdom and energy of the stakeholders. You can’t do alone and top down – you need the energy of all the stakeholders from citizens, communities – and all the co-investors which entails the huge complexity of stakeholder networks in urban environments. There is creativity and energy that needs to be tapped into, in order for these transitions to happen. We have to acknowledge that there are a lot of troubled relationships, for example between the stakeholders and centralised city government, which are currently too distant from knowing the local community and its needs. This too is in a transition and it’s good to learn lessons from other cities from these topics.

What is your favourite city and why/what can we learn from it?

I love a lot of cities: there are always inspiring things happening anywhere you go – whether it’s smaller towns and villages, the largest cities or the suburban areas – I would dare to say – despite my childhood “trauma”… there are great communities everywhere and I feel very privileged that I can work in many inspiring cities across the world and in the Netherlands.

My hometown is Amsterdam – and I really love living here: we get all the culture you can imagine and it’s like a global village. It’s a great base to move around to other cities and while think I could easily feel home in many cities, Amsterdam is one city where living is easy. I think there are a lot of the elements of the 15 minute city already in place. For example, I have raised two children in Amsterdam, they are young adults now but already the age of 8 or 9 they were cycling to school independently. The freedom, for both the child to gain independence, and for adults, for not having to drive the children to school was absolutely great. These are basic aspects of human scale, but they mean so much. We also have lessons to learn from other cities, but I think Amsterdam’s human scale is something quite unique.

What I love in Amsterdam are the street scapes – and that’s how I think it differs from quite many cities. People take over of the public space in a casual and cosy manner – and private mixes with public in a great way.

That’s a good point – we often focus on the cycling-topic for example, but I would also point out the informality: people placing benches and plants outside their door to have a positive influence in public life. This is deeply rooted to the Netherlands being a more citizen society already since the 16th century with certain anarchy, instead of a noble, royal or religious society. The squatters of the 80s are now sitting in local councils for example, so the connection to the people’s society is strongly there in many ways. Of course, the pressure is on here too: the market forces are very strong and there is a lot of pressure on housing prices – and so poses a lot of challenges too. There are major societal and political challenges as everywhere in Europe.

What other cities have intrigued you recently?

I was recently visiting Wroclaw, in Poland, one of the partners in the Cities in Placemaking network, which is a wonderful city: I was amazed about the inner city and its human scale. They have great public places, great in winter time too and full of life, despite cold weather. It is also a city with officially 600-700.000 residents which has in the last few years grown with about 200.000 Ukrainian refugees – isn’t that amazing? It’s puts us to shame here in the Netherlands as we make a fuss over allocating housing for 1000 refugees… It’s so impressive how Wroclaw managed to absorb hundreds of thousands of new people in the city. For example they created this welcoming centre for new people who are arriving to the city and it is located in a very central underpass space. They opened up the windows, it’s really part of public life and not hidden fourth floor somewhere in an office space. I think that already tells you a lot how they approach this topic of social places and how people are adopted in the city.

The city is super open for creating more welcoming public spaces and therefore is also investing in placemaking. They see public space as an extension of social places, place for integration and so on. I was very impressed by this and how the city poses an example instead of the “usual suspects” of urbanist’s, like Berlin. I was very much inspired how progressive the people working for the city are, politicians and the civil servants, eager to learn and how to accommodate the lessons of placemaking in their own city. This doesn’t mean that there aren’t any conflicts, in fact conflicts are part of cities, it is more how do you deal with the conflict.

We are happy to hear about your views about how we work in urban environments: Do you see potential in solutions like Parky for developing urban environments?

I think if you work with transition, you have to be part of the swarm, the flock of moving birds. This means that as a city government you have to be super networked and really connected to the local stakeholders to co-create the city. If you work for a city government, and when you go the local neighbourhood, there can be distrust based on prejudice, but also past experiences of the citizens. In order to build those networks and be influential in those networks you need find ways to build trust. And in my view, how do you build trust: not just by talking for three years, but by doing stuff together, by co-creating actual change on the short term. When an idea pops up to turn a place around, a public square for instance, you can’t afford to wait for three years before you have discussed, designed, found funding for the implementation – and people are then quite often disappointed with the results.

Doing stuff together and to build trust is the whole idea of tactical urbanism – it is a deeper mindset for creating an environment where you test and learn and tap into local energy quickly. You need to do urban actions in a much more iterative way, get quick results and build on those for larger investments. You will see, that you can implement so much more together with the citizens when you are part of that swarm and can tap into the stakeholders energy. And that’s the context where I see Parkly. I think Parkly has it in itself the quick & flexible: to be there in couple of months, rather than in couple of years and you can easily move it around and iterate if needed. Once a city has done for example a pocket park in a certain place and moves on for the more permanent implementation, it can then use those same moveable furniture elsewhere – and that’s part of the charm.

For me the opposite of top down planning is not bottom up, but it’s “middle-up-down”, where you create an equal platform for the local energy as well as the top down, long term investment strategies to collaborate and co-invest. You bring those two together and these kind of tools can make that happen while building on the local energy. Most of these kind of projects are liked by the locals and pave way for something bigger – which is the essence of transition.

What is the most important topic at the moment for Dutch cities in terms of developing them towards greener, healthier and social?

We have a lot of advantages in these terms: we have our bicycle networks, parks, sidewalks – but then again, this is not enough. We know more and more about urban health, but still we see that for a large part of population the health is in decline, especially in the lower income neighbourhoods. This is something we can’t accept. While this is a complex issue with social aspects too, it also comes down to the influence of the kind of neighbourhoods people live in. The lower income neighbourhoods are the more stoney ones, lots of stoney public spaces, so also the hotter ones in the summer, and the ones with fewer amenitiessocial . That’s an area where we should help as placemakers to turn this around: to build local connections and networks with the local population for more inclusive city making. For me placemaking is not reserved for nice urban beach type actions in cities, which are as such positive things, but it is the neighbourhoods and areas where it’s needed the most where we need to be. It’s said that the Netherlands in ten years will have the climate of Paris and probably in 20 years the climate of Madrid – so we do need much much more to have more green in these neighbourhoods. When you walk around the historic parts in a city like Amsterdam, you might think all is well here, but when you go to the outer neighbourhoods, you will see a whole different reality. If you manage to add more green and create inclusive places as a city, you will create better opportunities for the people who live there.

Dream big! What does an ideal future city look and feel like?

If you Google “future cities”, you get images of flying cars, lots of towers of steel and glass – which I hope is not going to be the future city. I hope our future cities are going to be very human scaled one, where people interact and meet each other. This very often happens in the inner city but the challenge is to take that feeling in outer communities, and create equal opportunities there.

I am very inspired by Singapore, where I have had the opportunity to work in the last couple of years. 30 years ago, Singapore stated that it is not a “garden city”, a city with just nice parks, but from then on it will be a “city in a garden”. That means that everything has to be green: all the roof scapes, all streets and facades and if you build a tower on a green space, you have to build more green space inside and, on the roof and on the facades and invest in the greening of the space around the building. They really made that part of their language and if you do that for 30 years you create an environment for a change in a vast scale.

If you compare it to Kuala Lumpur, which same climate as Singapore, it can be even 10-15 degrees celsius hotter city. Kuala Lumpur has not done much in terms of climate transition and there is a lot of asphalt which absorbs the heat and for example walking is uncomfortable in the heat, whereas in Singapore people are walking much more because it’s comfortable. This comparison shows that it is a choice and defining what kind of city you want be? City with traffic jams and people stuck in their air conditioned cars or a city which has comfortable to environment to walk and cycle around. It’s about making the sustainable choices it practical: people cycle in Amsterdam not because we are bicycle advocates, but moving from one place to another is just quicker on the bike. These are choices that we can make in our cities for future cities.

Read more!

www.stipo.nl