In this interview Matt Grunbaum, landscape architect and associate partner at Field Operations tells about his work, the New York High Line and how connecting to the site and communities is the essence of designing great places. The interview was conducted during the Utopian Hours city making festival 2024 in Torino by Päivi Raivio.

How did you become a landscape architect?

Growing up, I was always drawn to something artistic, and that’s where my interests naturally gravitated. Landscape architecture first came up when I was exploring university courses, but honestly, I didn’t fully grasp what it entailed until about six months into the program. Our lecturer started introducing us to a mix of projects, including Dani Karavan’s land art, and Martha Schwartz’s projects. This playfulness with design kind of stripped the boundaries of what landscape architecture could be… These examples showed me how sculptural and dynamic landscape design could be, and my interest really took off. I studied landscape architecture in University of Canberra, a small class – just about 12 graduated. Where the university sits is surrounded by bushland – and you have kangaroos bouncing around the campus! Having that kind of nature and landscape just outside the doorstep certainly left a mark on me.

Later on I had the opportunity to work at Oculus in Sydney, which had an amazingly collaborative and creative studio. They had a very thoughtful and unique approach to designing furnishings and integrating elements into landscapes – combined with their attention to layout – this left a strong impression on me. From there, I traveled to New York in 2005 or 2006 and visited MoMA, where I encountered the High Line exhibit. The project hadn’t been built yet, but the exhibition displayed the design, and it was like nothing I’d ever seen and I told myself I’d come back to work with that firm. Seven years later, I landed a position at Field Operations and have been there ever since.

Landscape architecture has been a journey of continuous learning and progression. When I started, much of the focus was on designing gardens and plazas. Now, we’re looking at city and regional scales, exploring how landscapes, public realms, and urban nature fit into the bigger picture. Topics like mobility, ecology, and even retail are increasingly linked to the profession, and landscape architects have the skillset to approach these complex scales. What excites me is seeing this progress and growing as both a practitioner and alongside the evolving industry.

“As landscape architects we have the ability to create a platform for public life to unfold. ”

As an associate partner Field Operations: how do you see the intersection between city making, civic engagement and landscape architecture? These are topics you touched on in your keynote talk too.

I really think landscape architecture is bigger than just designing parks and gardens – that it is the whole public realm which is stitching the whole city together. Through this lens, you consider a broad range of aspects, themes, and fields of expertise. In our office, we use a great diagram to illustrate this – it maps out the diverse professions and areas of expertise involved, from civil and structural engineering to horticulture and ecology and more. As a landscape architect you have to be able to collaborate and connect with all these experts to design and deliver these complex projects. You don’t have to be expert in all these fields, but you have to understand them enough to kind of collate them in to make the public realm work, to make the civic spaces work.

How can landscape architecture address some of the most pressing challenges facing cities across the globe today?

Connecting with nature is a major focus in this field. The importance of nature for health and well-being as well as practical urban solutions – like cooling cities and managing water. As cities face challenges from climate change, we look to natural systems to act as infrastructure, handling water surges and other climate-related issues. Increasingly, we’re finding that nature-based solutions can often address problems that were once solved purely by engineering. Furthermore, they can become great public spaces, it’s a three for one for cities.

Are there some new innovations which are emerging? Or is it or should it be more about “the basics”?

I feel like we forget the basics. Sometimes we look to technological solutions, forgetting what cities – and people – actually need. Ultimately, we’re trying to create spaces that are healthy, where people can connect with nature, socialize, and let public life unfold. Much of this doesn’t require technology; it requires well-designed, comfortable spaces. While new technologies and data analysis are exciting and useful tools, they can’t replace these foundational elements – it’s a combination of these things.

You mentioned in your keynote talk the prompts, from the community, from the site and its history, you use in the design work. How do you collect or identify these prompts?

Another great thing about landscape architecture is that you work in a variety of places, a variety of cities, a variety of communities and different cultures. Every place you work in is very different, you can’t apply the same thing in New York as you do in Torino or in another city, they are fundamentally different places. First thing we do is look at the site, research the history, talk to the community, understand the wants and needs and then start to piece out how we can interpret that information and start designing the actual site and play that back to the community and get their response. So I think the critical thing, and the beautiful thing, about our work and the industry is that everywhere is very different, the approach and the design should be too.

The HighLine is a great example of the urban transformation or transitions for the industrial landscape and infrastructure. Where do you see potential for the next sites, which come available through structural transformation?

That’s a good question. I think there are several fronts cities have to be actively developing. One key area is connecting more with their water systems to manage rising sea levels, storm surges, flooding, and other climate change impacts. Large infrastructure projects should prioritize nature-based solutions at scale – these not only protect urban areas but also provide valuable public access to natural spaces, especially along waterfronts. Another shift is how cities are moving away from tearing down buildings and building new: instead, focusing on reuse and circular economy. Anything we can do to help the climate is the future.

What is your favorite scene, anecdote or memorable moment from visiting or being at the HighLine?

Oh, there are a lot of memories and memorable moments, and I used to live very close by too. One event that they had there that I thought was very special is the Mile Long Opera (Watch the clip below). So, at night time you would be able to walk along the High Line and the community opera singers, scattered through the whole length. Some of them were hidden in the planting, some were visible right in front of you. It was really immersive, it was kind of an unworldly and very surreal experience. Experiencing the park through these kinds of sounds was very memorable to me. It is a really cool thing with the public realm, it can change so much through events and activities.

We work in public spaces, focusing on urban transformations and tactical interventions using flexible, modular furniture systems rooted in systems thinking and placemaking. How do you view the potential of tactical actions in shaping future cities through process-driven approaches or experiments?

We often refer to these as early works, where we establish a program with the client before any actual building or design begins. This phase involves observing how people use the space and gathering insights to shape the design. For instance, at Domino Square, our client built a temporary BMX bike track, which encouraged people to visit the area through quick activations. By the time construction starts and the project is completed, people have already formed a connection with the place. These quick, light interventions are also effective for activating spaces, especially when city budgets are tight.

What is your favorite city and why?

I will say New York, because that’s where I live and that’s my home. But the thing about New York which I think is amazing, is the energy it has. I don’t think I have ever found that in any other city. It’s hard to define exactly, but when you’re on the streets, you feel it all around you. And you kind of take the energy, and give it back – something is always happening. It’s a very diverse city, for example when you go out to Queens, one of the most diverse places in the world. Having all these different cultures, foods, textures, languages – and all of that in a melting pot. It makes New York very unique and fascinating. It has what I call “a happy chaos”.

What does an ideal future city look and feel like to you?

I don’t think an ideal city exists – everyone’s vision of it is different. Ultimately, there are always improvements we can make, like increasing affordability, enhancing diversity, equity, and equality, and improving access to public spaces and mobility. But I don’t believe there’s a single, ideal city. They should all be different, that’s what makes cities amazing.

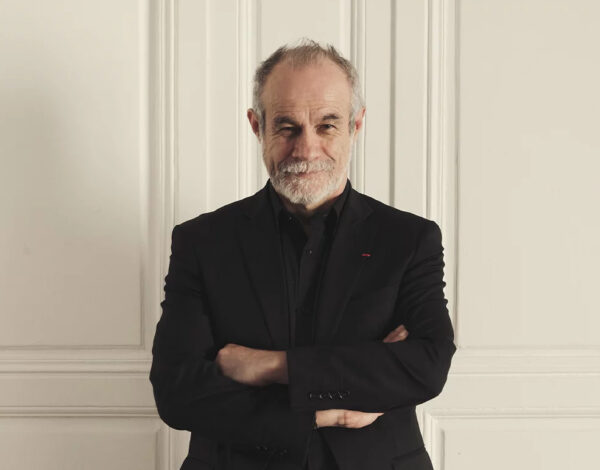

Matt Grunbaum is an Associate Partner at Field Operations and has been practicing Urban Design and Landscape Architecture for over 20 years. He believes in the power of a quality public realm to transform the health of our cities. His work is inspired by the fusion of place, ecology and the human experience. Matt leads transformative work in London, Birmingham, New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. Formative projects include Camden Highline, Smithfield Birmingham, Tonva Park and Navy Yards Central Green.

New York High Line

Nearly 20 years ago, Friends of the High Line looked to transform the High Line into public open space. A design competition was held in 2004 and won by the team Field Operations, Diller Scofidio + Renfro which partnered with the iconic garden designer Piet Oudolf. Their design took inspiration from the High Line’s original self-seeded landscape to create a stunning, multi-layered garden experience with a dynamic trail of spaces along the 1,5 mile long park – one the most iconic public realm projects to date.

Read more about the The High Line

Field Operations

Watch a clip of the Mile Long Opera