Petra Marko is an architect and placemaking expert whose work focuses on shaping and promoting people-oriented cities and inclusive public spaces. She is co-founder of Marko&Placemakers with offices in London and Bratislava and strategic lead on place projects at visual design studio Milk, where she led the research and co-authored Meanwhile City, a best practice and how-to guide for temporary interventions. Petra sat on the UK National Infrastructure Commission Young Professionals Panel; taught at The London School of Architecture and co-authored VeloCity, a strategic vision for rural areas. She is a member of Westminster Council’s Design Review Panel, providing independent advice on major regeneration projects in central London.

Tell us a little bit about yourself

I’ve trained as an architect and focused since on the ‘in between’ spaces – public spaces and infrastructure that enables walkable and livable neighbourhoods. I grew up in Bratislava, studied architecture in Vienna and Stockholm and ended up in London for over 15 years. The financial crisis in 2008 hit London hard and opened up questions around the changing role of architects. This was an important junction on my journey. I embarked on a masters’ degree in Creative Entrepreneurship to become more skilled in interdisciplinary collaboration, leading me to work on the client side as design manager for a London housing developer unlocking small sites; and later to set up my own placemaking practice, Marko&Placemakers, with my partner Igor Marko.

I love London’s intensity and diversity and I am lucky to have met and worked with some exceptional people along the way. My professional women’s network through cycling has become particularly important as I navigated career and parenthood. With my partner we were keen to bring back our expertise to Central Europe and started to grow our work across masterplanning and public space projects in this region. We set up a branch of our practice in Bratislava, which offers us great quality of life as a base with our 7-year old and enables us to engage more directly in further transformation of the city.

Why (or how) did you become an architect and placemaking expert?

At school, I was first fascinated by photography, the play of light and shadow, which is really about capturing space, but also about capturing its mood or feeling. Photography is rather ephemeral, yet very concrete. This led me to consider architecture quite early on. At university, I was drawn to all projects ‘in between’ buildings – if you look at the so called Nolli plan [Giambattista Nolli, 1748], which first plotted built and unbuilt space of the city in a map without the kerbs and street lines – you can see that public space is virtually everywhere in between. This opens up the possibility to interpret street design differently, and we can see it play out in form of street markets on weekends for instance, when suddenly people criss-cross everywhere and the entire street becomes full of life. I was also fascinated by the hidden story of places, and why some places seem laden with character and emotion, whilst others might be beautifully designed yet don’t prompt the same reaction or relationship.

When I was in Havana, I was fascinated by the Malecón, an 8km seawall promenade crushing the open waves of the ocean. This tree-less, bench-less promenade next to a four-lane road is the most popular public space in Cuba. Malecón is a symbol of freedom, a place from which some have tried to escape in boats, and countless others come to watch the sea horizon, beyond which an idea of a different world exists. Imagination is a very powerful tool. Placemaking is not just a spatial design practice. It is about uncovering the hidden meaning which makes up the identity of the place and its people. We need to be sensitive to these symbols and hidden meanings when transforming places.

What is your favourite city and why/what can we learn from it?

In London I feel the kick of energy and pinch myself every time I’m on the underground sharing space with such amazing diversity of people. Fast paced and highly competitive, London quickly forces you to discover your edges. But I think London’s intensity also moves people towards greater empathy and tolerance – whether it is in sharing space, or in collaboration across professions. On a neighbourhood level, London is a series of villages, and our village, Bermondsey, for instance, is very central yet very local in its character. When our son was little, I have discovered every nook and cranny of our hood and was amazed at how much more there is locally that I did not know of before. If we can learn something from London, I’d say despite all its crisis and challenges it would be the capacity for tolerance and embracing of diversity.

The main downside of London for me is that it is really hard to get away from. It takes hours by any means of transport to get to the countryside or seaside, and it is often easiest to fly, which is not good for the planet! Bratislava as my new base now gives me that freedom to hop on a train and be not just in the countryside but even in another country in a short space of time. When it comes to quality of life, the proximity of nature, including lakes to swim in, is fantastic. It really has ingredients of the 15minute city. What we can learn from Bratislava at this current point in time is that despite many mistakes and problems along its evolution, with the right leadership [Bratislava’s architect mayor Matúš Vallo is in his second term now], a city can shift its balance and turn the tide – in case of Bratislava towards people-oriented public spaces and embracing of its architectural heritage.

You are the co-author of the book Meanwhile City. How did the idea for the book develop and what did you find out while making it?

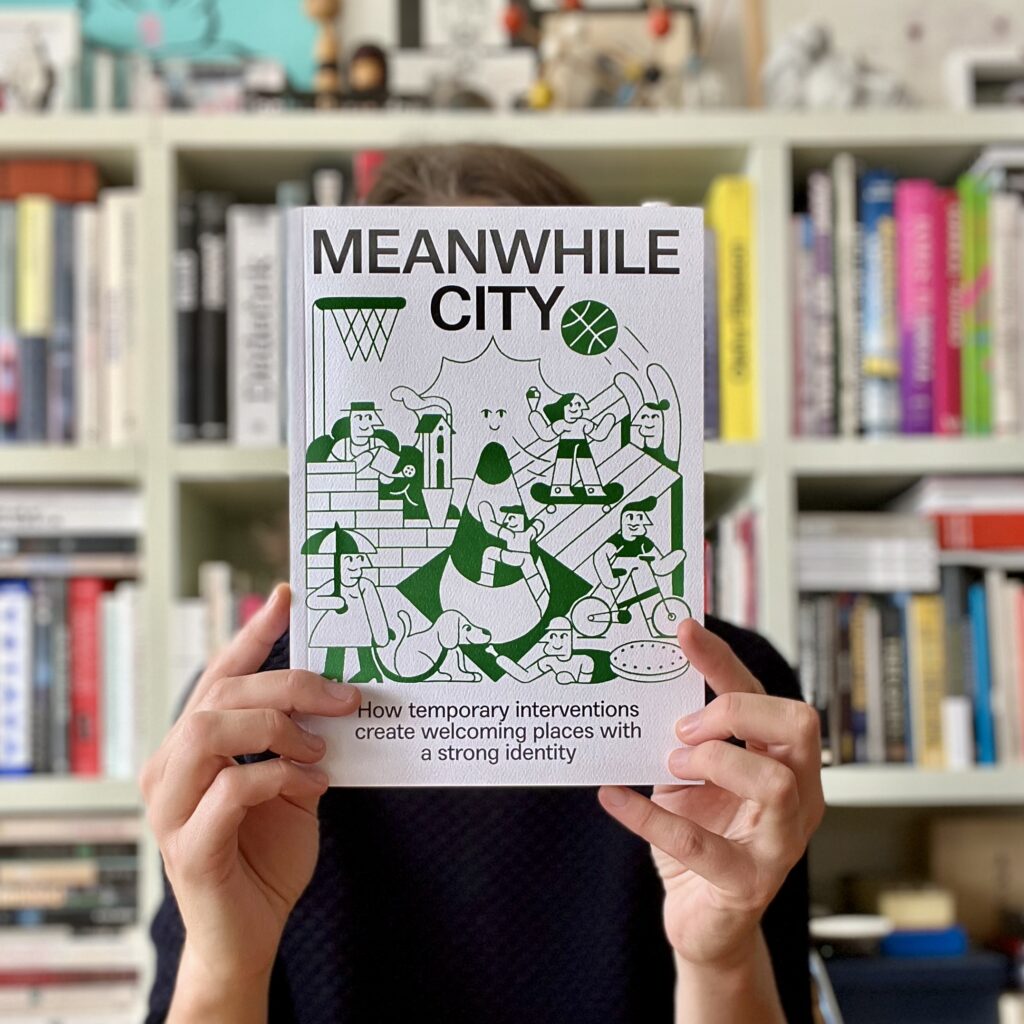

Martin Jenča, the founder of Milk [a visual design studio based in Bratislava], approached me in spring 2022 to set up a dedicated Places team at Milk. The intention was to not only help tell stories of great places, but also to shape their content through temporary activation. Meanwhile City was a starting point on this journey, and as someone who was very familiar with meanwhile projects in London, and someone who also loves researching and writing, I was immediately on board. We wanted to make a book that will be easily digestible for wider audiences without dumbing down the subject topic and show that tactical urbanism is not just a stop gap, but an important strategic tool for municipalities, developers and citizen initiatives in long term transformation of cities and in achieving behaviour change.

Working with Milk’s team of editors, illustrators and graphic designers, I think we succeeded to push something which is still a niche industry topic into an engaging and playful format which for instance caught the eye of Monocle and is included in Space10’s curated selection of 100 essential books for creating a better everyday life for people and the planet in Copenhagen. Meanwhile City is an opener for conversations with local authorities, citizen initiatives and developers on how to make temporary steps that can support long-term visions for more welcoming places.

Do you see potential in solutions like Parky for developing urban environments?Absolutely. Cities need to focus on climate adaptation as climate emergency is no longer a distant problem but a lived day to day reality. Whilst increasing soft permeable surfaces to prevent heat islands, planting trees with sufficient tree pits and greening the city are some of the main long-term solutions, a lightweight movable system like Parkly which integrates greenery and shading can go a long way in acupunctural transformation of places, testing how footfall and usage of the space changes, and building case or even attracting funding for long-term transformation. Social value is another important aspect of street furniture – creating places where people can meet, elderly can sit or youth can hang out freely without the need to buy anything opens up public space to more users, more ‘eyes on the street’ [coined by the late urbanist and activist Jane Jacobs], which all creates a more welcoming and more inclusive neighbourhood.

What is the most important topic at the moment for a city such as Bratislava in terms of developing it towards a greener, healthy and social city?

From my perspective, active travel needs to be one of the main priorities for Bratislava – that is creating a substantial safe and continuous cycle path network, strengthening public transport provision, and creating walkable neighbourhoods, alongside campaigns to encourage greater uptake of commuter cycling. There is still huge dependency on private cars in Bratislava, and a very high percentage of car ownership in Slovakia overall, linked to the culture of the car as a status symbol, whereas cycling is perceived mainly as recreational sport rather than an efficient and convenient way of moving around one’s daily needs. I feel safer on a bike in London, though there is visible change under way in Bratislava nowadays, including a newly implemented regulated parking policy, a growing cycle path network and revitalisation of public spaces. It is fantastic the city has recently won a 3-year consultancy support from Bloomberg Associates, a team of experts who stood behind transformation of New York City’s streets and plazas, who will help Bratislava to fast track these changes.

Dream big! What does an ideal future city look and feel like?

I think there really is nothing like an ideal city, and never will be. Otherwise, the whole world would have moved to Vienna by now, which by most charts is the ideal place to be. I love what Fran Lebowitz said about New York City: “No one can afford to live in New York. Yet, eight million people do. How do we do this? We don’t know!” [Pretend It’s a City, documentary, 2021] Cities are spatial and human organisms, and everyone’s experience of their city is highly individual and based on personal relationships. The older I get, the more I tend to lean towards the relationship aspects of placemaking. We can’t deny that our upbringing and our cultural background shape who we are, no matter where we later make a life. I watched the documentary about Arnold Schwarzenegger recently. His house in LA looks like a supersized Austrian cottage – in his own words combining the Austrian cosiness with the American size! Isn’t it fascinating we seem to be on our way home, no matter how far we get from it?