Walk and talk through the Superblocks with Silvia Casorran Martos, urban planner and sustainable mobility expert in Barcelona.

Barcelona is an intriguing city, especially when it comes to its unique urban structure and density. The efforts to create a more livable city through urban transformation projects have become exemplary in many ways. Superblocks, known as Superillas in Catalan, are among the most referenced tactical urban projects in recent times.

During a recent visit to Barcelona, I had the opportunity to stroll around Superilla San Antoni with one of the key figures in the project: former deputy chief architect Silvia Casorran Martos. She now works as public servant in sustainable mobility for the Barcelona metropolitan area, and loves biking through the city.

Earlier in the day, I met with some planners involved in tactical urbanism projects, some of which aim for large-scale transitions. It was enlightening to connect our discussions with the real environment: understanding the complexities of creating a place, maintaining it, dealing with tumultuous local politics affecting the projects, and identifying the necessary solutions in different climates.

We convened at 6 pm in the main tactical square of Superilla San Antoni. Contrary to my assumptions, it was actually one of the busiest hours. Children of all ages were playing and moving around, people were sitting, eating, playing cards, or simply crossing the square. There were sounds, connections, and movement—a vibrant square.

Silvia pointed out that the “open-ended” public furniture elements played a significant role in enabling this liveliness. These elements could be used in various ways, including playing, sitting, lying down, and many other actions people could come up with. This aligns with Parkly’s philosophy which stems from its founders experiences in placemaking; despite or perhaps because of the simple forms, people can shape them into what they desire. Kids love playing with “simple stuff,” climbing, jumping on and off things, playing hide and seek, and more. Imagination is sparked when we have to transform things into something, rather than when elements are already defined. There is a certain flexibility that traditional public furniture, like benches with armrests, lacks. While traditional benches are great, variety is needed, especially in transformation projects, to enable more ways to reimagine and test different ideas and functions.

“We believe that the tactical implementation of this Superilla square fulfills many public needs. Unfortunately, some politicians and more conservative users perceive the colorful, “untraditional” furniture as not being of “high quality.” However, we aim to emphasize what it enables: more public life and connections.” Silvia says. This point became evident when we walked to the next square, the permanent implementation on the square named Conxa Pérez. While it is inviting and has ample seating—a very positive feature, especially compared to its previous state—it was quieter, lacked movement, and had no children present. This sparked a discussion on how we should incorporate elements of semi-temporary or temporary tactical urbanism actions, where people play a key role in making it their own, into the more permanent or permanent implementations. It also raises the question of what constitutes high-quality public space, especially when certain user groups like children are not utilizing the more permanent installations. This differs from many squares I have seen in other districts, for example. Playful elements have been included in many squares in the Gracia district, and some traditional squares are in their simplicity like playfields themselves, introducing a unique kind of coexistence. We also discussed the idea of profiling different squares: a green “biodiversity” square, a playful square, a calm square, and so on, while keeping a good mix of uses in mind.

“Projects like these tactical initiatives are crucial in pushing cities to act quickly and learn through experiments faster. There is urgency, and we need the right tools to address this urgency,” Silvia pointed out, referring to climate change and other significant challenges facing our cities. Unfortunately, recently, these projects have been significantly impacted by local politics: since the new council started last June 2023, many public place improvements were put on hold, despite substantial data demonstrating the benefits of the projects—less pollution, more social connections, increased footfall for local businesses, and enhanced safety. “It’s a lot about communication: what’s possible, what are the goals—and this is not something slow development projects can convey.”

Greening Barcelona

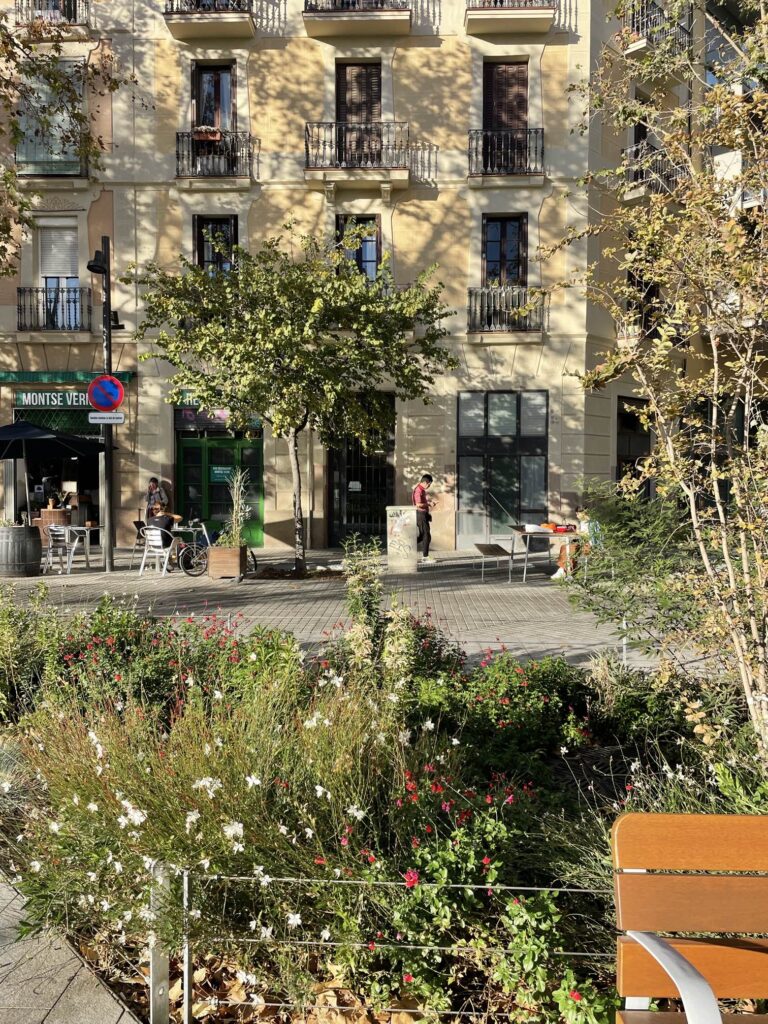

Embarking on the green corridor of Consell de Cent, which spans an impressive 3.8 km through the district of Eixample, we also delved into the city’s urban greening efforts. Barcelona is an impressively green and diverse city, and the significance of greenery is widely recognized. However, the city grapples with water scarcity, forcing challenging decisions on excluding plants and trees from certain plans due to the high pressure to conserve water. “Keeping the trees alive is a challenge in the summer, and for any planters and other green elements, we should choose plants that can withstand as little water as possible,” Silvia pointed out.

Some SUDs (Sustainable Urban Drainage systems) and other water conservation efforts have also been introduced. Addressing the water scarcity issue while expanding greenery, especially as climate change progresses, poses a significant challenge with no direct answers. The city’s impressive tree count of about 320.000 trees spanning almost 500 species is truly one of the key networks in the city to cool it down in the summer. New trees are planted but preferably directly in the ground; planners have discovered that in this climate, trees thrive and grow better when not initially grown in planters – however planters can still have higher plants and bushes and for example those in Superilla San Antoni looked lush and provided shade too.

Elements of the 15-minute city

“Barcelona is a fifteen-minute city,” says Silvia, pointing out how people can find most services within a short distance from where they live and work. I am told that an impressive more than 60% of all commuting movement is done on foot. This is visible on the streets, and all paces and age groups are welcome when the faster modes of transport are not mixed too much in the pedestrianized area. Silvia also points out that with more space and a slower pace, people tend to look up more often, admiring architecture and facades, and examining their surroundings – and in Barcelona, there is a lot to see and discover!

The active plinth space in the green corridor also caught my eye: from a language school, bakery, repair shop, cafes, restaurants – public life is vibrant, and the benefits are manifold. Citizens enjoy calmer, quieter, and cleaner streets, while local businesses benefit from people using the city at eye level. “The quality of public spaces is very important in a dense city like Barcelona; it is an extension of their home, as many live in small flats.” – a lesson for all cities, which are getting denser: the quality of public space has a huge impact in people’s lives.

Learning from Barcelona

After the walk we sat down on one of the many cafes which are sprawling to the street space and talked more about the lessons from Barcelona to other cities.

“Is there a way to ensure commitment from all stakeholders despite potential interference from local politics, which can greatly impact the completion and scaling of urban transformation projects? The evidence supports the benefits: less pollution, more social connections—what arguments exist against these projects and how to overcome them?”

“In the end, all around the world we always share the same resistance about taking space from the car. This is amazing because in cities most of people do not drive a car, even do not own a car. But the “car-centrism” has been in our cities for more than 50 years now, and this phenomenon is very difficult to revert because of the current economic interests behind this. Probably we need to communicate better about social and environmental benefits of active mobility and about the bad impacts from motorized traffic. Why advertisements tell us about dying when we smoke but not when we drive a car? Media is still telling us that driving a car make us freer, more beautiful, more powerful… we should stop this!”

“More and more cities are advancing urban experiments and tactical actions to accelerate the development of public spaces and create more liveable cities – and to address the urgency. What are the key obstacles in scaling them? Is there something planners and decision-makers can prepare for to make the process as smooth as possible?”

“Some people still think tactical actions do not have enough quality to change urban space. But thanks to these actions we can act fast in making our cities more liveable: more space for people, less pollution, less noise, less crashes… the biggest challenge in my opinion is keeping the greenery in good conditions while it lives in just pots and not properly planted in the earth.

In the case of Barcelona tactical actions cost us between 1/10 – 1/5 of the cost of structural actions. We should ask ourselves: how much money and time do we have to transform our cities? Of course tactical actions can be develop into structural actions, but once they are there then there is no urgency anymore: we have more time once the bad impacts of the current public space are gone!”

“Cities and public places are complex entities, with different interests of stakeholders converging at this interface. How can we form a shared vision? One would think all stakeholders agree on a cleaner, safer, and more comfortable public realm?”

“All political parties and stakeholders should sign an agreement to provide healthy and sustainable cities. That is the key: they should all agree in protecting citizens’ health.”

“And lastly, can you share your best memory from the Superillas? I have visited them just a few times, but for me, the most memorable thing was the happy coexistence of people, some playing cards, some eating, some chatting, and kids playing together. I can imagine, this is a place, where kids can make new friends – a great criteria for any neighbourhood!”

“When the pilot Superblock in Poblenou started, in 2016, I was living in that area. I remember very well the first time a neighbor told me, at the street: “I have seen your daughter just a few minutes ago”. Hanna was then 11 years old, and did not have a mobile phone yet. I was very amazed and happy that the new social life at the street (thanks to the new public space for people) made suddenly a safer / more secure public space, especially in gender terms.”

Interview was conducted and edited by Päivi Raivio

Photo of Silvia: Chris Bruntlett

Photos from the locations: Päivi Raivio and Jonathan Zoccoli

Explore the Barcelona Biodiversity Map